What to Know

- Congestion pricing would impact any driver entering what is being called the Central Business District (CBD), which stretches from 60th Street in Manhattan and below, all the way down to the southern tip of the Financial District

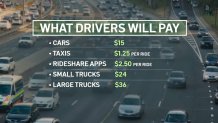

- Passenger vehicles would be charged $15, trucks would be charged anywhere from $24-$36 depending on size, and motorcycles would be charged $7.50.

- Taxis face a $1.25 surcharge per ride. The same policy applies to Uber, Lyft and other rideshare drivers, but their surcharge will be $2.50.

The prospect of congestion pricing coming to New York City just got a lot more real, as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) board overwhelmingly voted to approve the measure it says will contribute millions of dollars for the city's aging transit system — and cut down on traffic — by charging drivers to enter a large swath of Manhattan.

The approval came after the Traffic Mobility Review Board delivered its report to the MTA on Nov. 30, laying out the general guidelines for the impending tolls, including costs, when certain prices will be in effect, who gets credits and more. Cars will be charged an additional $15 to enter Manhattan at 60th Street and below, while trucks could be charged between $24-$36 dollars, depending on size.

(For more information on surcharges, exemptions and when the tolls will be in effect, scroll down.)

Get Tri-state area news and weather forecasts to your inbox. Sign up for NBC New York newsletters.

"Right now, we are very much ready and excited to accommodate the projected movement of a portion of the driving public to transit," said MTA Chairman Janno Lieber. "We do have plenty of room on transit, but that does not mean that we're going to stop pushing to increase service."

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, who has been a vocal supporter of congestion pricing, hailed the board's approval.

"Congestion pricing means cleaner air, better transit and less gridlock on New York City's streets and today's vote by the MTA Board is a critical step forward," Hochul said in a statement. "The proposal approved today heeds my call to lower the toll rate by nearly 35 percent from the maximum rate originally considered."

Only one member of the MTA board opposed the plan when it was put up for a vote Wednesday morning. The other nine members voted to approve the plan.

"$24 — that's what it will be to go in and see a son or daughter, or to see a show, or to have dinner. I cannot vote for it, I'm sorry to say," said board member David Mack.

It wasn't all good news for subway riders on Wednesday: Due to lawsuits and other slowdowns to approval, the MTA said they are delaying a promised re-signaling of the A and C trains between Manhattan and Brooklyn. The transit agency said the evidence of how important such work is can be seen in the wait time improvements along the L and 4/5 lines.

Here's a breakdown of everything that was approved on Wednesday, and what comes next in the process:

How does congestion pricing work? Who gets charged — and how much?

Congestion pricing would impact any driver entering what is being called the Central Business District (CBD), which stretches from 60th Street in Manhattan and below, all the way down to the southern tip of the Financial District. In other words, most drivers entering midtown Manhattan or below will have to pay the toll, according to the board's report.

All drivers of cars, trucks, motorcycles and other vehicles would be charged the toll. Different vehicles will be charged different amounts — here's a breakdown of the prices:

- Passenger vehicles: $15

- Small trucks (like box trucks, moving vans, etc.): $24

- Large trucks: $36

- Motorcycles: $7.50

The $15 toll is about a midway point between previously reported possibilities, which have ranged from $9 to $23.

The full, daytime rates would be in effect from 5 a.m. until 9 p.m. each weekday, and 9 a.m. until 9 p.m. on the weekends. The board called for toll rates in the off-hours (from 9 p.m.-5 a.m. on weekdays, and 9 p.m. until 9 a.m. on weekends) to be about 75% less — about $3.50 instead of $15 for a passenger vehicle.

Drivers would only be charged to enter the zone, not to leave it or stay in it. That means that residents who enter the CBD and circle their block to look for parking won't be charged.

Only one toll will be levied per day — so anyone who enters the area, then leaves and returns, will still only be charged the toll one time for that day.

The review board said that implementing their congestion pricing plan is expected to reduce the number of vehicles entering the area by 17%. That would equate to 153,000 fewer cars in that large portion of Manhattan. They also predicted that $15 billion would come in from the plan, which would be used to modernize subways and buses.

"Excess traffic is costing the New York City region $20 billion a year," said Kathy Wylde, of the Traffic Mobility Review Board.

Do Uber, Lyft and other rideshares get exemptions? What about taxis?

There will be exemptions in place for rideshares and taxis, but much to their chagrin, they won't get away completely scot-free.

The toll will not be in effect for taxis, but drivers will be charged a $1.25 surcharge per ride. The same policy applies to Uber, Lyft and other rideshare drivers, but their surcharge will be $2.50.

New York Taxi Workers Alliance Executive Director Bhairavi Desai said in a statement that the plan is " a reckless proposal that will devastate an entire workforce."

Are there any other exemptions to congestion pricing tolls?

Many groups had been hoping to get exemptions, but very few will avoid having to pay the toll entirely. That small group is limited just to specialized government vehicles (like snowplows) and emergency vehicles.

Low-income drivers who earn less than $50,000 a year can apply to pay half the price on the daytime toll, but only after the first 10 trips in a month.

While not an exemption, there will also be so-called "crossing credits" for drivers using any of the four tunnels to get into Manhattan. That means those who already pay at the Lincoln or Holland Tunnel, for example, will not pay the full congestion fee. The credit amounts to $5 per ride for passenger vehicles, $2.50 for motorcycles, $12 for small trucks and $20 for large trucks.

Drivers from Long Island and Queens using the Queens-Midtown Tunnel will get the same break, as will those using the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. Those who come over the George Washington Bridge and go south of 60th Street would see no such discount, however.

Public-sector employees (teachers, police, firefighters, transit workers, etc.), those who live in the so-called CBD, utility companies, those with medical appointments in the area and those who drive electric vehicles had all been hoping to get be granted an exemption. But neither the MTA nor the Traffic Mobility Review Board included any such exemptions for those groups.

There is some concern regarding enforcement. The MTA has already struggled to collect at cashless toll plazas with up to 5% failing to pay.

"We are gonna go after it hard, and make sure they’re not getting away with it. The credibility is the whole effort is at stake," Lieber said about those who try to dodge the toll.

So what comes next, and when will the tolls go into effect?

As for when the plan could go into effect, the MTA has maintained that the goal is to start charging the toll in late Spring 2024. But it's likely that will be delayed a bit.

Now that the MTA has approved the initial plan, there will be a 60-day response period in effect, which will include four public hearings in late February and early March. Any possible tweaks to the plan (like Mayor Eric Adams' request for more exemptions, for vehicles such as taxis) could be added before what would be a "final" vote in April.

That would mean the earliest the tolls would actually go into effect would be late June 2024, at this point.

There had been fears of a toll as high as $23, but MTA Chairman Janno Lieber previously poured cold water on that idea, saying earlier in the year that MTA board members were "trying to keep it well lower than that." He added that in order to keep the standard toll price low, the transit agency would have to keep the number of exemptions low as well.

But even with the lower recommended prices, local leaders from both sides of the political aisle were already looking to take legal action to prevent the congestion pricing plan from charging their constituents.

"It’s ripping off New Jersey commuters to pay for whatever financial hardships the MTA is facing. We’re considering all of our options, including further legal action," said New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy.

Gov. Murphy previously sent a letter to the Traffic Mobility Board asking for drivers from his state to be exempt, arguing they shouldn’t have to pay for the toll to take the Holland and Lincoln tunnels or George Washington Bridge in addition to an extra fee to go into midtown Manhattan. He argued that toll price should count as a credit toward the fee, to ensure they are not having to pay twice.

New Jersey has filed a lawsuit against the federal government in an effort to block congestion pricing. Staten Island has said it plans to sue the MTA over the plan as well.

"The recently-reported $15 toll to enter Manhattan below 60th St is nothing short of complete highway robbery for the people of Staten Island. This could be one of the worst things to ever happen to Staten Island," said Staten Island Borough President Vito Fossella. "We have said time and time again that all Staten Islanders, especially those who live near the Staten Island Expressway, will have to suffer with more air pollution and more traffic, not to mention this added tax to travel within their own city. For all this, Staten Islanders will see no return on the investment they’ll have no say in making."

Any one of the lawsuits filed against congestion pricing could also bring the plan screeching to a halt, depending on how the judges rule. Many of the challenges focus on the environmental impacts of the plan, though proponents have said it will help cut down on emissions.

Aside from legal challenges, one of the only ways to keep the plan at bay would be some sort of act by Congress or the federal government.

The New York City Council held a hearing on the matter late over the summer. Transit President Richard Davey testified at that hearing, saying the revenue generated from the plan will help make NYC's transit system state of the art — which will benefit everyone.

"That is what congestion pricing is going to buy, investment in our transit system. So we’re excited about taking this next step in the approval process," said Davey.